Contemporary Viewing Stones Displays

While it is beneficial to understand and be able to practice traditional Chinese and Japanese viewing stone display methods, it is equally important to have the ability to utilize more modern display methods that suit our modern lifestyles. Our homes, cultures and virtually every aspect of our modern societies are radically different from the traditions and life of the Qing dynasty or the late Edo and Meiji periods in Japan. Today most homes, even in Japan, do not have a tokonoma for the display of art objects. Nor do we have special buildings or large rooms appropriately equipped to receive guests as in traditional estates in China. Our living and working spaces have changed.

Contemporary viewing stone displays are not intended to replace traditional Asian modes of display; rather, the purpose is to expand opportunities for innovative displays that are more in keeping with our modern societies. This cultural adaptation is as fitting now as it was when the practice spread from China long ago.

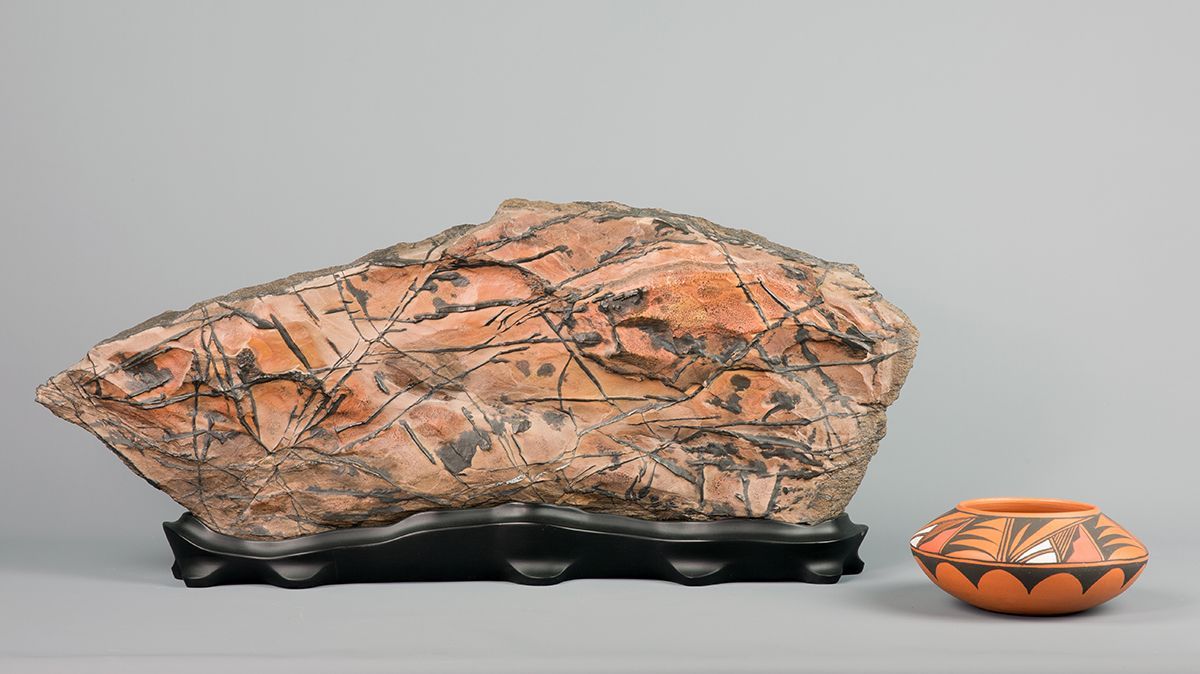

Today, there is a broader range of stones available to collectors, especially in many of the western countries. Furthermore, a wider range of accessories is available that better fit each country’s traditions, arts, and culture. In North America, the bison and American eagle are more suitable imagery than the crane and turtle which are more directly associated with Asian cultures. Encouraging potential stone connoisseurs to experiment with nontraditional approaches to display stones is an effective way of building a larger stone appreciation community. We expressed the hope in the book

Viewing Stones of North America, that contemporary collectors would seek ways to use native stones to create displays guided by local and regional influences. It is to be expected that the diversity of American culture would demand a variety of approaches to stone display.

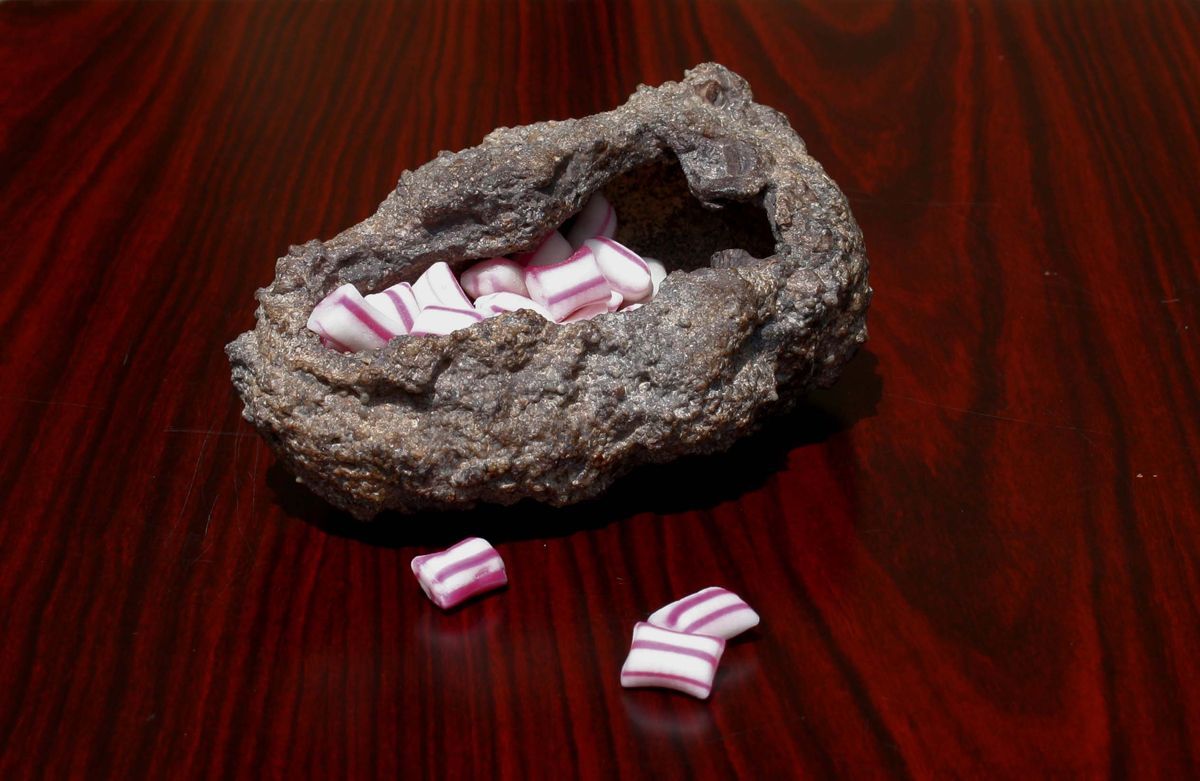

Rick Stiles wrote in the above book that a distinct North American stone appreciation tradition will likely be driven by three factors—geology, landscape, and idiom. Stiles used the word idiom as an expression that has a meaning different from the literal. He was opening the door for people to use different stone types to create exciting new displays.

Contemporary displays will be a major component of a North American stone culture. Likewise, stone enthusiasts in other countries can develop parallel cultures that incorporate their own distinct features that fit with their customs.

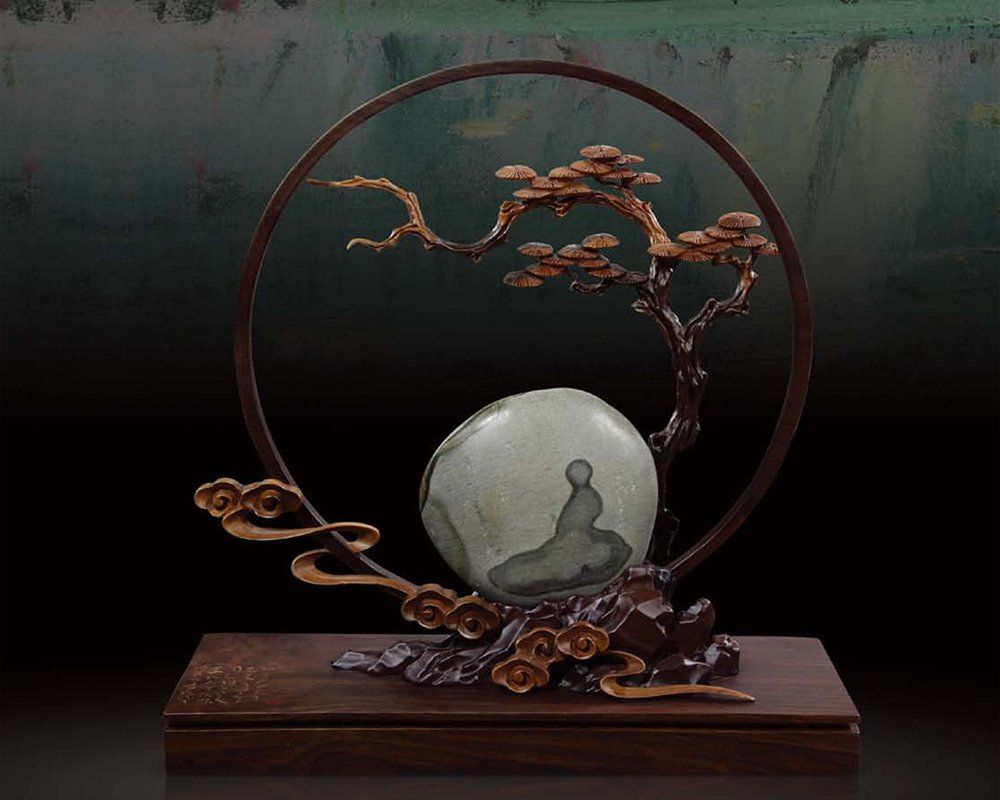

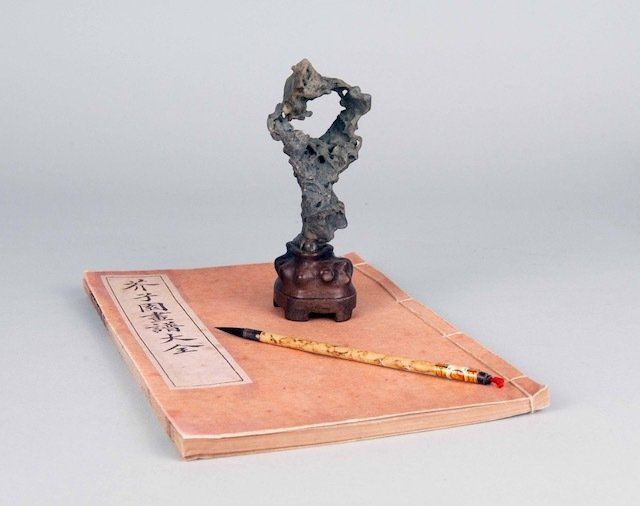

The California artist, Richard Turner, explores the relationship between viewing stones and contemporary art in an essay in the featured book of the month. He notes that viewing stones and contemporary sculpture have more affinities than first meet the eye. Turner considers viewing stones to be a form of found-object art and looks to the work of contemporary artists from Asia, Europe and America for inspiration for his viewing stone displays.

Now, viewers and stone collectors following our VSANA web site can participate in this newly evolving culture and can contribute to it by submitting photographs and descriptions of their creative approaches to contemporary stone display. Working together and featuring a different contemporary display each month will contribute to a truly exciting year for the advancement of stone appreciation worldwide.

Gallery of Contemporary Stones

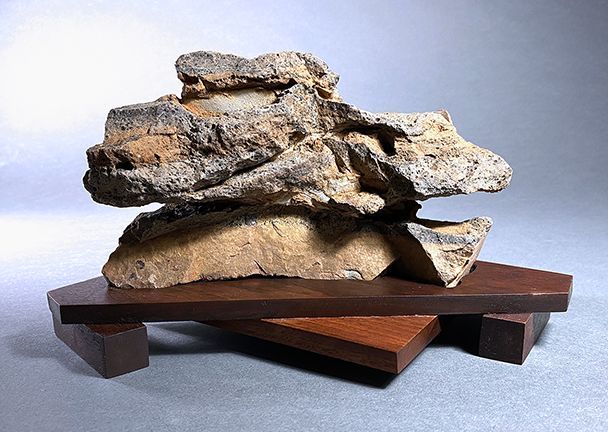

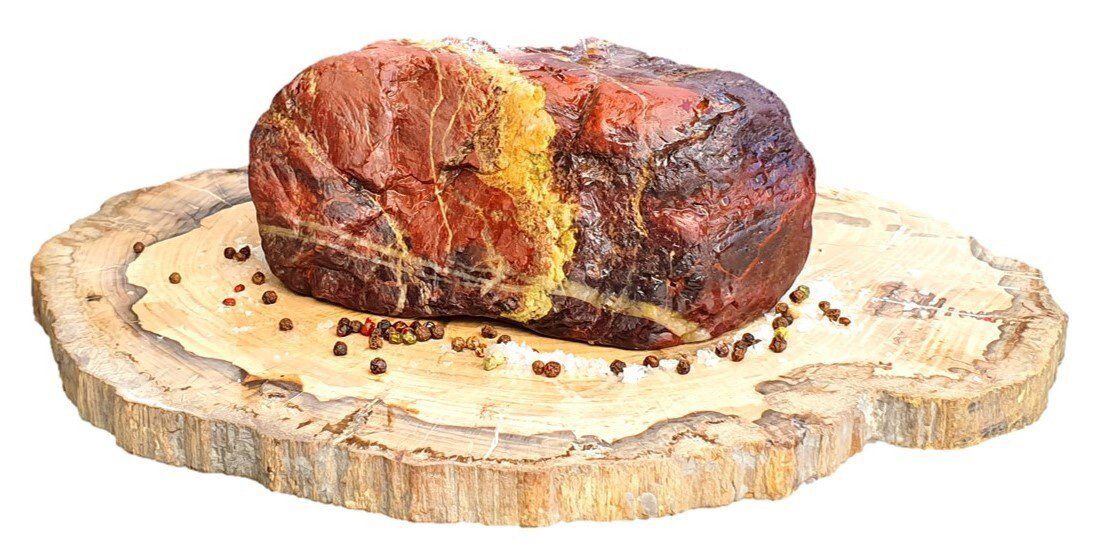

FROM WOOD TO STONE

By Michael Colella

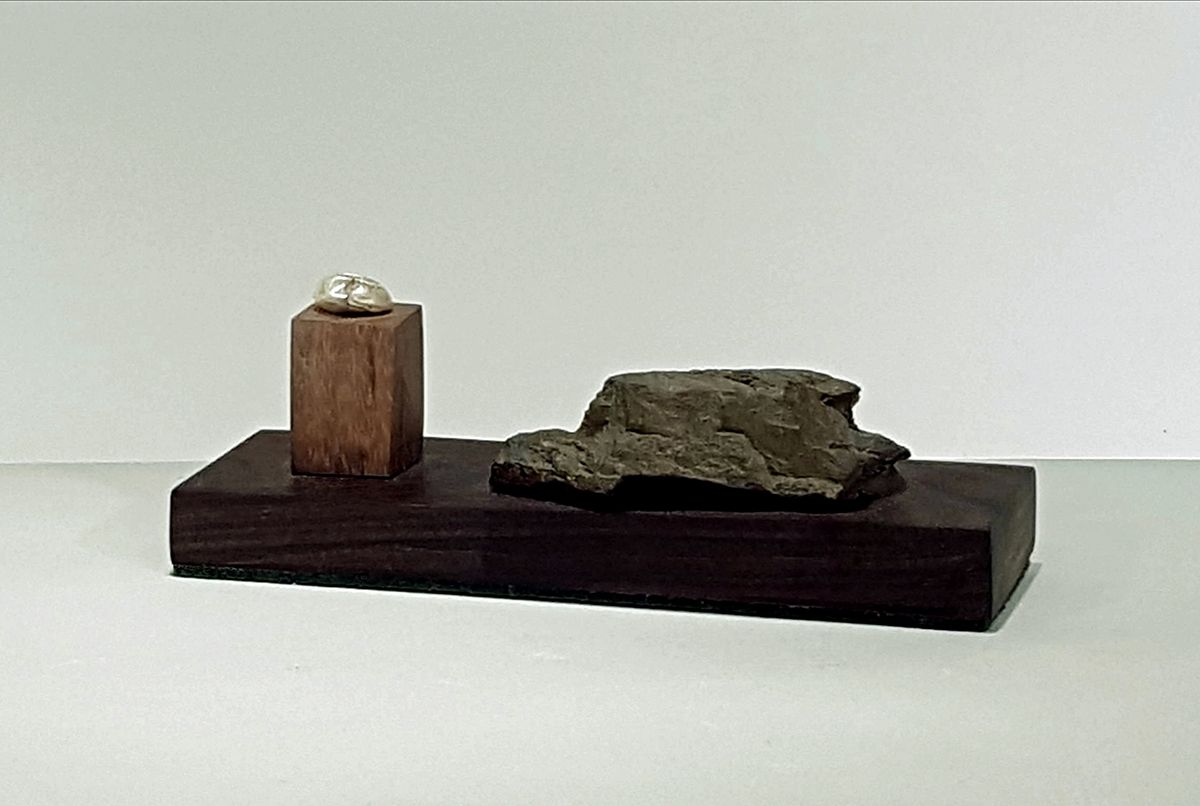

I began collecting rocks and minerals when I was a child and have continued this hobby into adult life. While browsing through stones at a local gem show about 15 years ago, I spotted this piece of petrified wood, which looked attractive to me but less so to others because it wasn't polished and shiny like all the other typical pieces of petrified wood on sale. By the end of the show, it was still there, so it had to come home with me. It sat in my collection for several years until I became aware of the art of viewing stones. Finally, my small petrified tree trunk would go on display. Also, as an avid woodworker, I had this piece of burl from a damaged branch of an old oak tree, which also had been sitting in my shop for years, waiting to be reborn. The two were a match. Pairing the natural cut off branch of the oak tree with the natural untouched petrified section of prehistoric tree branch made the perfect display of young and old. "From Wood To Stone" is the natural cycle of life in this viewing stone.

Stone: Petrified wood 4"D x 15" H, base - oak 6.5" D x 4.5"H.

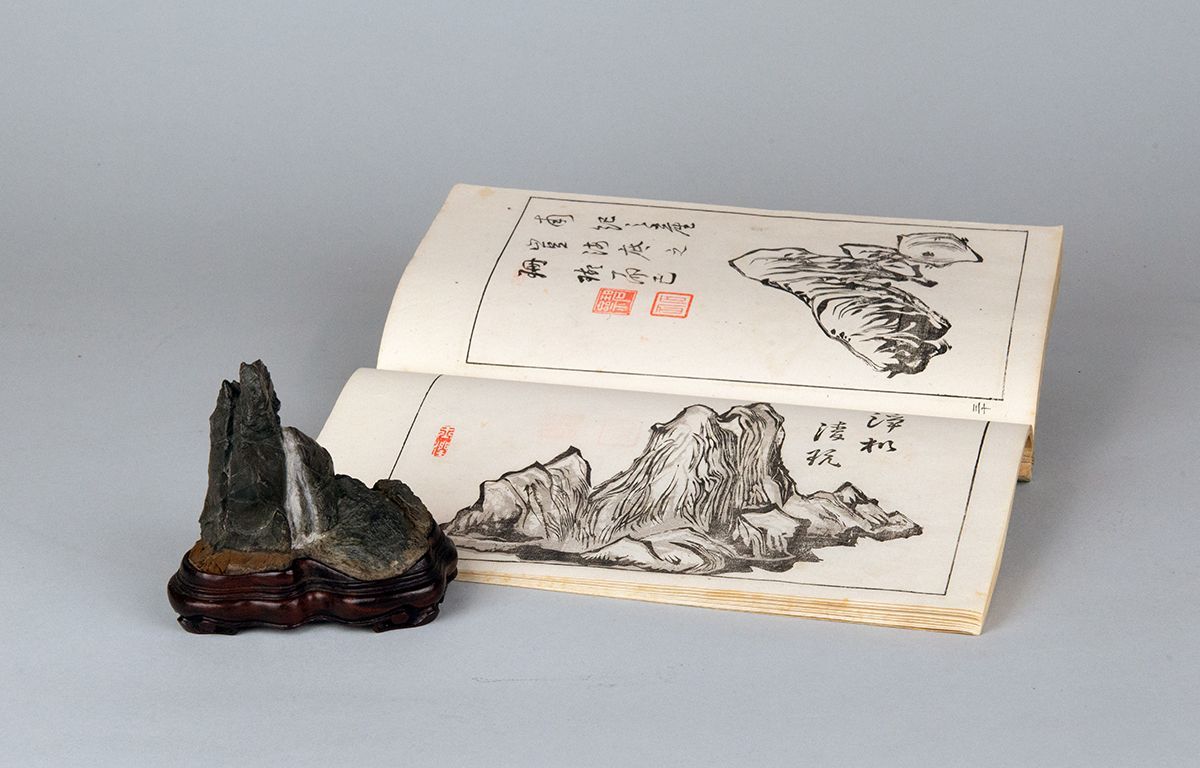

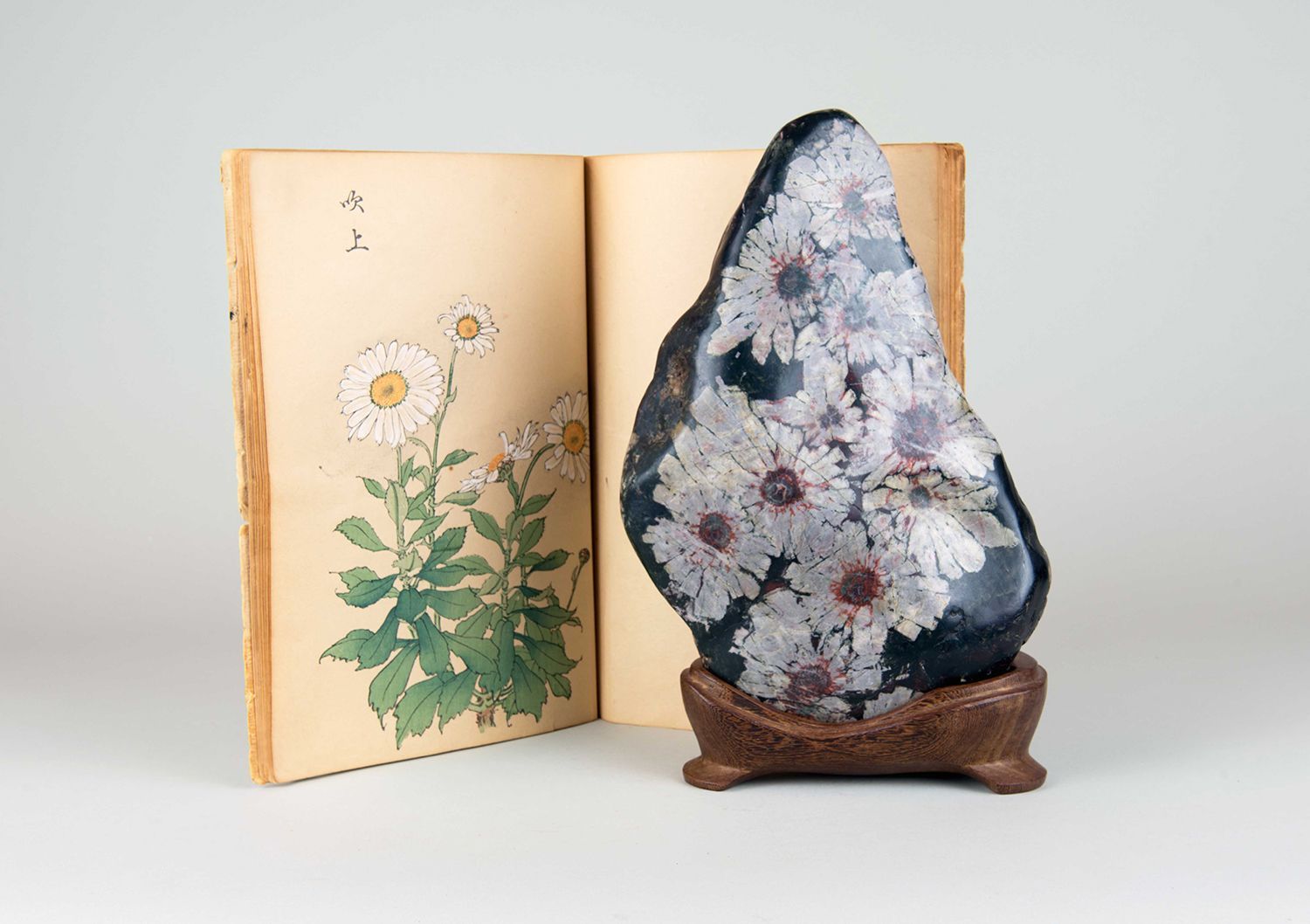

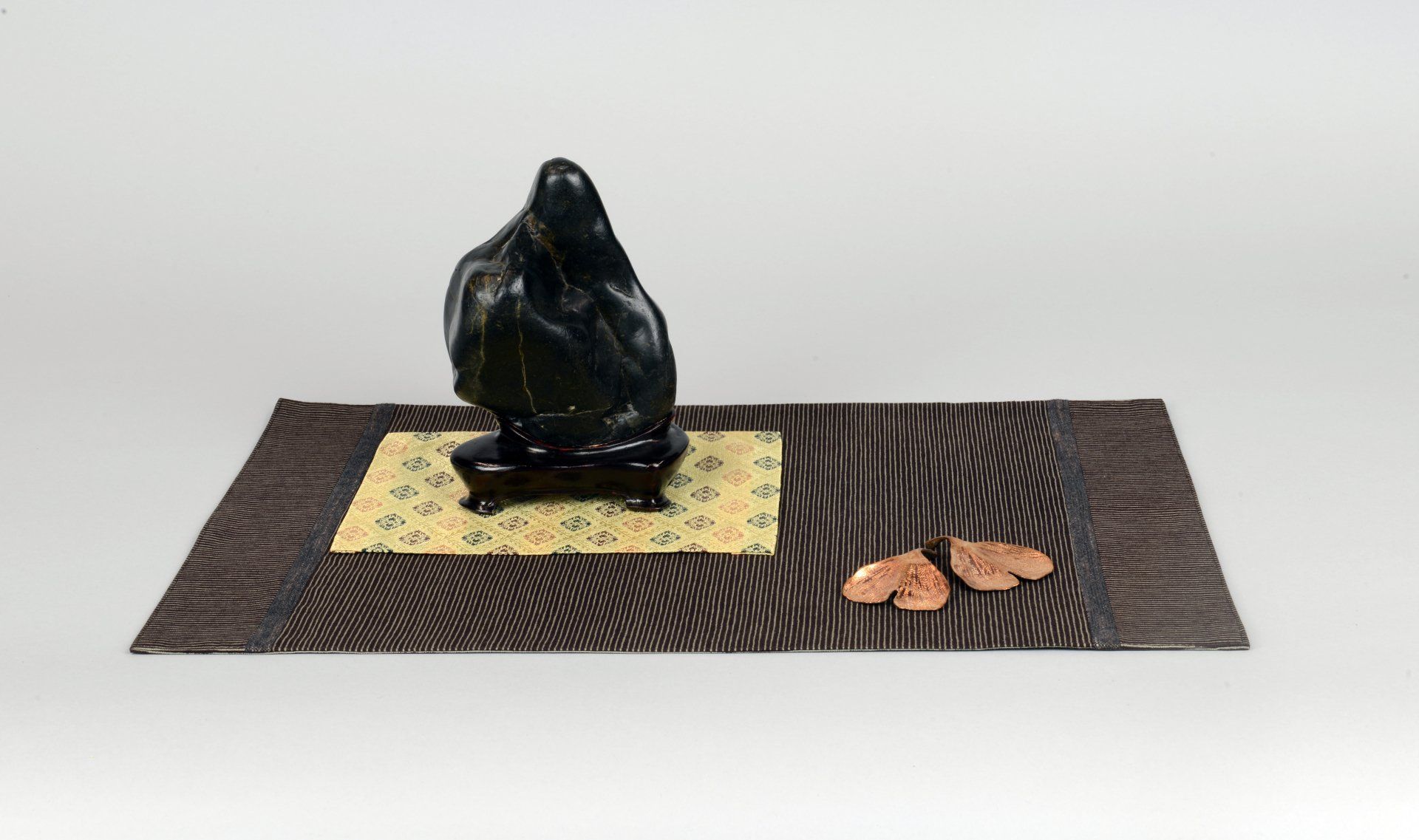

PEACE AND HOPE

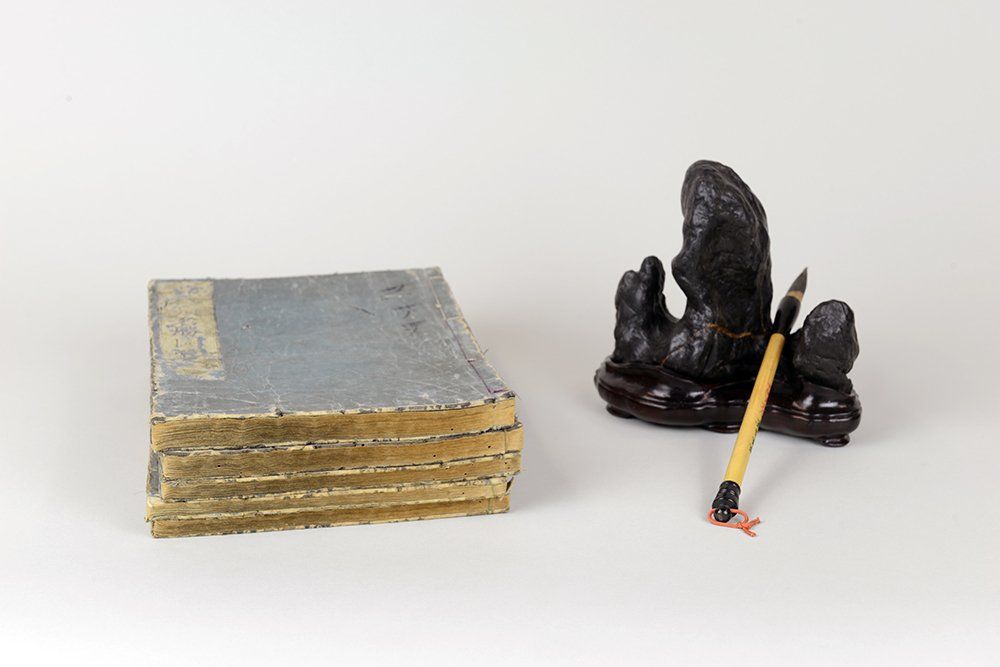

This black Japanese Kamuikotan figure stone represents a figure often seen at Buddhist temples—Kannon, Goddess of Mercy. Kannon is typically depicted as a slender statue in temples and gained popularity because she often answered prayers and created miracles. The stone and its base sit on a light color fabric that symbolically represent the pedestal usually associated with such figure stones. Two sculpted, gold-colored, gingko leaves complement the stone not only in form and color, but also symbolically. Gingko leaves and trees have a long cultural history in Asia as representing peace and hope. They are resting on a brown fabric mat signifying soil in which the tree is growing. The elements of this display beautifully complement each other to form a message much greater than the individual objects themselves. This display was created by Thomas S. Elias as part of a series of displays using fabric in place of display tables.