Going beyond the form to appreciate classical Chinese scholars rocks

A discussion of how to appreciate Chinese scholars rocks

By Joseph Roussel; photos by Laura Mah

Appreciation of classical Chinese scholars rocks is a complex topic. Many streams of thought encompassing philosophy, religion and art have contributed to over a thousand years of writing on scholars rocks. I will not seek to cover all these ideas or even dive deeply into one as this is the domain of experts who are far more qualified. My goal will be to share personal views on a key topic in stone appreciation: “going beyond the form” or not limiting your appreciation to only looking at stone shapes. By “going beyond the form,” you can also create a space for creative discussion where friends can meet and share their thoughts on what they see and enjoy when observing a scholars rock – a social practice integral to scholars rock appreciation.

Ying Stone (Qing dynasty or earlier) Guangdong province. This stone was a gift to the Musée Guimet, Paris from the Juxui Zhai (Gathering Elegance studio) collection.

Close-up of Ying Stone, Guangdong province (Musée Guimet, Paris). Looking closely, we see an almost metallic surface and multiple colors and shades.

An over emphasis on form or the “objectification” of rocks is not easy to avoid; it often comes from an understandable desire to see rocks as an art form. The very act of putting rocks on stands increases this challenge as stands fix rocks into one position and evoke the idea of a sculpture. When we give names to rocks, something I have certainly done, we also risk freezing rocks into a fixed image. While rocks are full of artistic interest and can inspire and stimulate our imaginations, I believe that their many qualities transport them into a unique category that goes beyond “art object.”

Ying Stone (20th century), Guangdong province, Juxui Zhai (Gathering elegance studio collection)

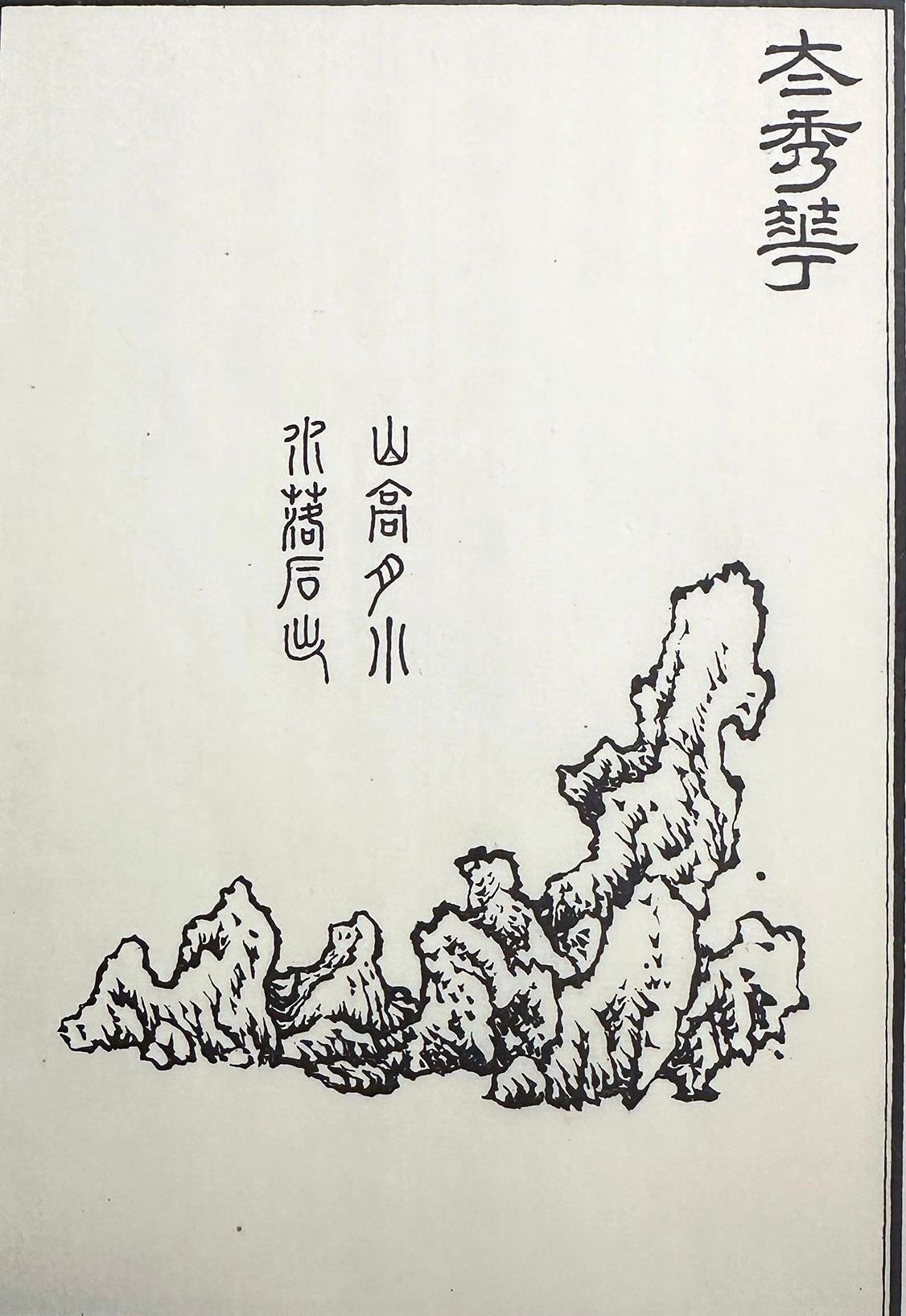

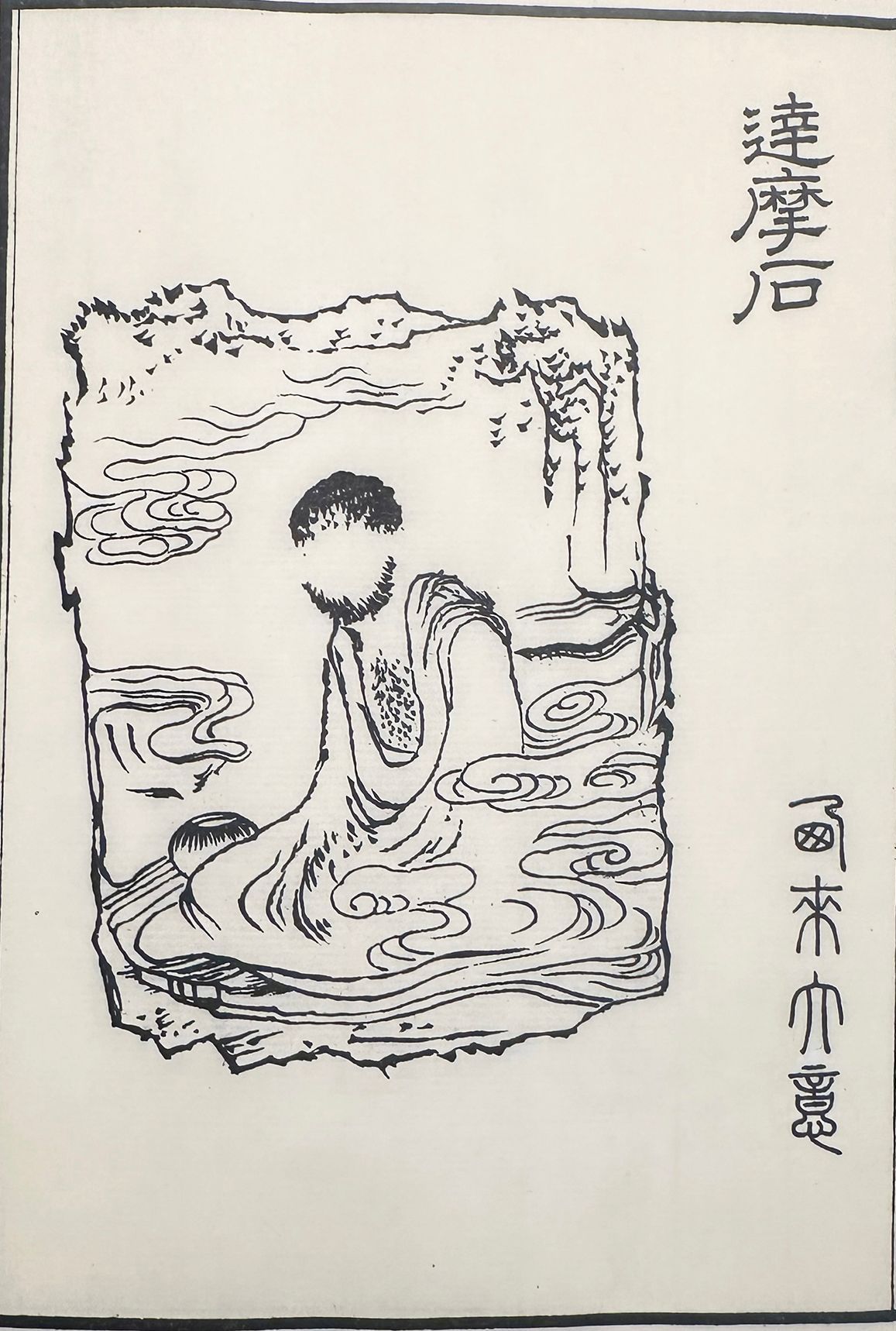

We should of course embrace the fact that form and color have always been criteria when evaluating rocks. The Suyuan Stone Catalogue by Lin Youlin (1578 – 1647) was written to document over 200 famous rocks. Multiple characteristics are describred in the catalogue including shape, size, color, functional use (ink stone, censor), sound when hit (mostly Lingbi stone), powers (“sobering up stone”), collector name, and place of origin.

Almost 50% of the rocks in that catalogue resemble mountains, and 15% are shaped like people, plants or animals. Around 10% have naturally occurring images on them such as a Dragon, Monk, a Bird, a Fairy, etc.

But just because the catalogue mentions shape doesn’t mean it was considered the primary criteria for appreciation. I believe it was just a practical way of identifying stones – after all, the primary purpose of the catalogue was to showcase notable stones for a broad audience.

Wen stone (Qing dynasty or earlier); Shandong province, Juxui Zhai (Gathering Elegance studio) collection. This small stone has three different textures and exudes great power although it can fit in the palm of your hand.

In his mid-19th century book Tanshi— or Chats on Rocks (quoted in John Hay, Kernels of Energy, Bone of Earth (New York City, China Institute in America,1985, p.38), Liang Jiutu stated that “in collecting, it is the choice of rocks that comes first. If the rock does not seem like a painting by the powers of nature, then you shouldn’t choose it.” My interpretation is that this refers to stones whose very essence connects us with the creative forces of the universe. If spring flowers and fall colors represent the fleeting world, rocks represent the birth of the cosmos. Their complex surfaces evoke nature’s processes and remind us of the complex transformations of the universe. Their surfaces can be described using wide variety of terms including wet, dry, veined, colorful, striated, fine-grained, lustrous, colorful, and dappled. Their varied textures can be characterized as wrinkled, rough, furrowed, pitted, dimpled, pockmarked, smooth, waxy, weathered. Through both touch and sight, we discover the creative results of destructive processes such as erosion and abrasion that made them what they are today.

Unknown type (Qing dynasty or earlier), China, Juxui Zhai (Gathering Elegance studio) collection. This highly weathered stone with its many cavities evokes movement and clouds.

The overall complexity of classic scholars rocks inspired the Chinese poet Pi Rixiu (834? – 883?) to write a poem The Lake Tai Rocks: A Product from the top of Sea-Turtle Mountain:

“ …the rocks must be the crafty tricks of Heaven;

Truly they cannot be the ingenuity of humans.

What do they look like?

Even a painter with supernatural skills could not picture them.…” Pi Rixiu (834?-83?) 皮日休

—Xiaoshan Yang. Metamorphosis of the Private Sphere (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2003), pp. 116-117

While there are many attractive and intriguing rocks, the rocks we most appreciate have a set of characteristics or “spirit” that remind us of the on-going transformations of the universe. We do well to create space for a dialogue with these ultimate time travelers who have witnessed millennia of great transformations. Their spirit calls for careful observation. Such observation forces us to slow down and retreat from our day-to-day busyness. As we clear our minds to engage with them, who knows what they will tell us?

Lingbi stone (20c), Anhui province, Juxui Zhai (Gathering Elegance studio) collection. This large stone has a tremendous variety of textures with both smooth and rough areas - it invites you to touch and explore its surface.